Blurred responsibilities and commercial conflicts of interest make this an unsatisfactory model for protection of investors in investment funds.

I argue that the principal reason behind the collapse of the Woodford fund is a governance model that is profoundly flawed since it is riven with commercial conflicts of interest. The FCA is reviewing the model. Let’s hope it can come up with something better.

Governance for OEICs (ICVCs)

In framing the governance structure for OEICs ,when these were first introduced in 1997, the industry, the regulator and the treasury debated whether requiring there to be individual directors of the fund itself would significantly enhance investor protection. This is a common feature of both the US registered investment company (‘RIC’) and the European SICAV. Against that is the fact that a fund board is composed partly of non-executive part timers, chosen by the fund management company, who rely entirely on the fund management company or sponsor for information, direction and compensation and partly of full time employees of the management company, who will be unlikely to challenge themselves. So, cynics argued, individual directors are an expensive luxury, who have to be paid quite large fees, supported with additional information and provided with independent legal advice. It is also argued that some non-executive directors may have too many directorships, perhaps few instances as egregious as the Cayman ‘jumbo’ directors who in some cases had hundreds of directorships. So overall there appeared to be little empirical evidence that individual non-executive directors’ efforts either to improve returns, argue for better products and improvements in service or reduce fees and costs had had any measurable results. Warren Buffet was once famously quoted as having said that is was as unlikely that a non-executive director would vote to replace an incompetent investment adviser as it would be for monkeys to type the works of Shakespeare. That is maybe too unkind to those who do their best.

The authorised fund manager/authorised corporate director (‘AFM/ACD’)

So the OEIC designers decided that instead of having fund directors they would transfer and adapt the familiar unit trust model where the fund management company had the principal responsibility for managing the fund, for ensuring that the regulations were being observed and that unitholders were being treated fairly. So the authorised fund manager (‘AFM’) became the corporate director of the fund (‘ACD’) thus in effect merging the responsibilities of management company, which managed, and the board of the fund , which supervised in the US RIC and European SICAV models. Now the AFM/ACD had the same responsibilities as if it was the management company of a unit trust. Lawyers also advised that it would be more likely to win compensation for investors from a well-capitalised fund management company than a number of individual directors in the event of a successful lawsuit.

The depositary

But how to answer to the conundrum ‘how can the fund management company supervise itself?’ because the AFM and the ACD are one and the same person. In other models of corporate funds such as the US RIC or the EU SICAV the fund directors supervise the fund manager or investment adviser. So in the new UK OEIC model the role of the depositary was given some weight and it was given the duty to oversee the ACD. The depositary also has a defined role in the European SICAV, which is convenient for adapting the UCITS directive into the UK regulatory rules, although it does not exist in the US RIC model, where supervision is entirely down to the fund directors.

The adoption of UCITS provisions in the COLL rulebook as they apply to both ICVCs and AUTs has a list of specific duties that almost all apply to both a trustee of a unit trust and a depositary of an ICVC. But this list fails to take account of the additional general duties of a trustee under trust law.

As the FCA COLL rule book puts it:

‘the oversight responsibilities for a trustee of an AUT are similar to, but not the same as, the oversight responsibilities of the depositary of an ICVC or ACS. These differences result from the different legal structure of the authorised funds and the trustee’s obligations under trust law.’

Our understanding of that is that a trustee has wider responsibilities than merely policing the specific functions listed in the rulebook. This may be why depositaries have failed to identify some notable failures, since they regard themselves only as having to obey the list of rules in in the rule book with a specific compliance role in relation to those rules only. .

A depositary must in discharging its functions act solely in the interests of the UCITS scheme and its unitholders. This concept of depositary derives from a much more rules based civil code environment, so those functions are set out precisely as can be seen from COLL 6.6B.16R. These are largely transactional rather than behavioural. There is no wider obligation to ‘ensure that the management company is acting in the best interests of unitholders at all times’. So a depositary has a narrower brief and less of an oversight role that makes it more of a securities administrator with some responsibility to supervise and identify any breaches of specific regulations. Looking at the website of a leading depositary the focus is largely on technical aspects of compliance with investment limits, valuation and pricing, without the overall common law responsibility that a trustees has.

A trustee not only owns and holds the assets on behalf of the beneficiaries and has to ensure that the management company is acting in the best interests of unitholders at all times without qualification but also has the ultimate power to replace the manager if the manager goes into liquidation, insolvency or receivership, or if the trustee believes that the manager is not acting in the unitholders’ best interests. This gives the trustee much more responsibility and power than a depositary. It is a holistic approach not just a compliance box-ticking approach.

The non-executive directors of the AFM/ACD

In its latest attempt to create proxies for itself by off-loading more responsibility and perhaps trying to mend the gaps in investor protection of the rather flawed AFM/ACD model, AFM/ACDs now have to have two non-executive directors. They are designed to enhance investor protection, presumable by ensuring that the firm on whose board they sit ticks the right regulatory and compliance boxes anddoesn#’t get into trouble with the regulator.

It is hard to see how these can have any impact when the AFM/ACD and the fund manager are fellow subsidiaries of the same parent, since, in our view, there are fewer commercial tensions in the internal model. In this model the AFM/ACD and the investment manager are under the ownership the same parent and thus they do not have a commercial fee paying relationship and there would be no consideration of one being able to hire, or possibly fire, the other. There is no need here for non-executive directors of the fund management company, since the owner of both can call all the shots even to the extent of getting rid of awkward non-executives..

However non-executive directors might add value to an external AFM/ACD service provider, whose directors are just accountants and administrators, particularly if they have some demonstrable knowledge and skills in investment fund management. It is too early to tell whether those engaged by rent-a-fund-manager companies will add value for investors. But it is as always hard to envisage non-executive directors biting the hand that delivers pay and rations – that is the fund management company and not, as in the US RIC model, the fund itself.

The investor protection consequences

The consequences for investors of the fragmented model in which responsibilities are divided between several players are to weaken their protection. While the lawyers and regulators will argue that responsibilities are clear, in commercial reality they are blurred in our view.

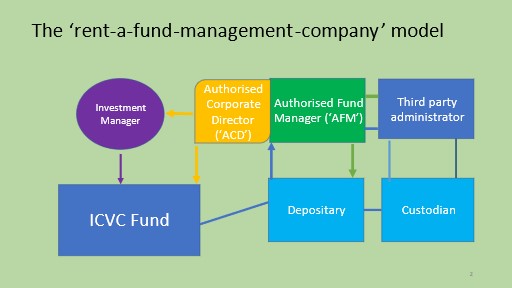

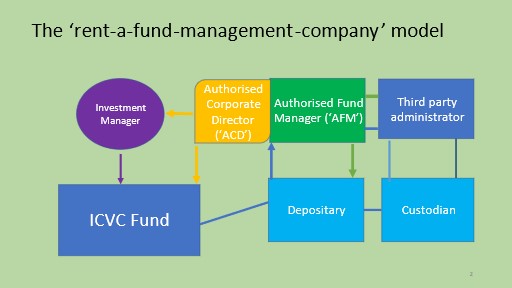

Let us remind ourselves of the model

Who will guard the guardians themselves?

Here is a spider’s web of contractual and fiduciary relationships, most of them with inherent conflicts of interest. Although this model applies both to external AFM/ACDs and to AFM/ACDs which are owned by the same parent as the investment management company, the tensions and conflicts are infinitely greater in the rent-a-fund-manager model.

This is the theory:

1 The AFM is in business to increase AUM and trade profitably but it is also ACD responsible for looking after shareholders’ interests

2 The ACD s compliance with certain rules is in theory overseen by the depositary

3 The AFM/ACD chooses and appoints the depositary but can replace it with another

4 The depositary may be able to replace the AFM/ACD

5. The AFM/ACD’s non-executive directors have divided loyalties

6 The AFM/ACD subcontracts the investment manager to manage the fund’s investments but could replace it

All of these contractual relationships are commercially driven. In particular the key relationship between the AFM/ACD and the investment manager. A specialised supplier of AFM/ACD services depends on attracting fund managers to use its services in order to stay in business. Although in theory it appoints the investment manager, in reality the investment manager picks the AFM/ACD that will offer it the best deal (or perhaps the least interference). The depositary is chosen by the AFM/ACD and can be replaced. In both cases there will be a certain unwillingness to bite the hand that feeds. And one may well ask whether many investment managers have been replaced by AFM/ACDs or AFM/ACDs by depositaries. Or how many depositaries have been replaced AFM/ACDS. Or how many AFM/ACD non-executives have resigned in protest.

It is becoming clear from as details of the Woodford affair become clearer that neither did the AFM/ACD, which was an external service provider to the fund, nor the depositary either realise that there was a build up of significant problems in the whole way the fund’s investments were being managed that could lead to failure; or, if they did, whether they contemplated taking action.

So what happens next?

The FCA is undertaking a comprehensive review of this governance model. My view is the unit trust model has greater clarity and simplicity with genuine trustee responsibility for ensuring investors’ interests are paramount; or, failing that, the US RIC model where directors of the fund have a definitive fiduciary-trustee role and are personally liable for failures. The Woodford affair exposed the conflicts and inconsistencies in the rent-a fund-manager model. It will be interesting to see what FCA comes up with; not deluging investors with ever more disclosure documents, we pray. Something needs to happen since the rent-a-fund-manager model is a truly horrible British fudge.

Like to know more?

If you want to know more, we examine different models on our online training course.