No clear responsibility

The key principles that underlie most investor protection or ‘treating customers fairly’ can be simply expressed. Here are some practical things a fund management company can do to attract and retain the loyalty of its customers.

- Give the customer what they paid for

- Don’t take advantage of the customer.

- Offer the customer the best product you can.

- Pay claims promptly and fairly.

- Do your best to resolve complaints as quickly as possible.

- Show flexibility and consideration towards your customer.

- Be clear and transparent in all your customer dealings.

But there is a lack of clear definition of responsibility in a fragmented governance and distribution system, given the profoundly flawed ICVC/ACD structure and the tortuous and sometimes obscure route by which investment services are delivered to end investors. See my comments on this under recent blogs at markstgiles.com ‘a flawed model’ and ‘the system leaves small investors out’. This not only looks like an impenetrable jungle to the average investor but also makes it hard for even the most sharp-eyed regulator to assign blame if things go wrong.

It’s all common sense. Expensive poorly performing products, sold hard without regard to customer needs, with lack of clear descriptions about objectives and risks that play to consumers’ ignorance will end up alienating customers, advisers and commentators in the media. So, if any fund management company gets a reputation for consistently failing to do any, most or all those things it will eventually go out of business.

Does it need to be spelt out in such detail?

Does a regulator really need to define what specific actions should be taken to ensure that these essentially commercial actions are taken by fund management companies in accordance with a detailed standard formula? The FCA has tried to do this by issuing sets of ever more detailed rules of conduct. But do these really protect investors? Sure, they make it hard for fund management companies to pinch the dough, but then it always was. Are investors really now treated more fairly as a result?

Well apparently, not. The FCA’s never tires in its missionary zeal to protect consumers but it acknowledges its failure fully to convert the heathen in its latest consultation paper.

https://www.fca.org.uk/publications/consultation-papers/cp21-13-new-consumer-duty

It says that even after years of effort there are still:

- firms providing information which is misleadingly presented or difficult for consumers to understand, hindering their ability to properly assess the product/service.

- products and services that are not fit for purpose in delivering the benefits that consumers reasonably expect, or are not appropriate for the consumers they are being targeted at and sold to

- products and services that do not represent fair value, where the benefits consumers receive are not reasonable relative to the price they pay.

- poor customer service that hinders consumers from taking timely action to manage their financial affairs and making use of products and services or increases their costs in doing so.

- other practices which hinder consumers’ ability to act, or which exploit information asymmetries, consumer inertia, behavioural biases or vulnerabilities.

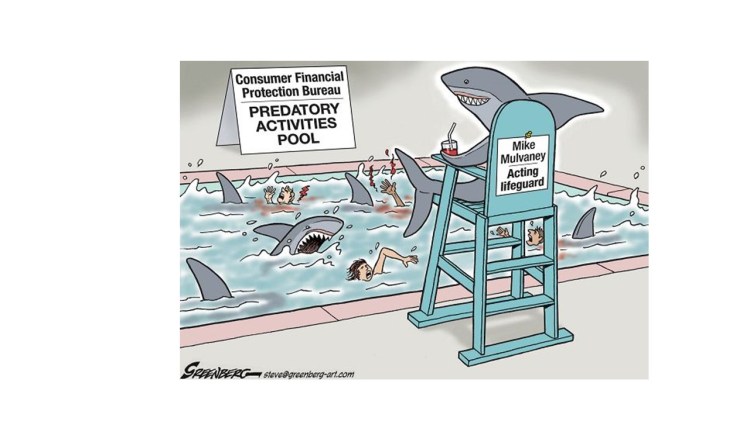

End customer bottom of food chain

The way in which funds are bought and sold makes it more complicated than need be. The end customer is so far from the fund management company that it doesn’t know who its customers are.

It is the way in which distribution is structured in the UK that gets in the way of fund management companies who are trying to ‘treat customers fairly’. End customers ‘belong’ to the distributors – platforms, advisers, discretionary fund managers and institutional investors. So, the fund management company is having to comply with an increasingly complex and extensive array of extremely detailed regulations designed to make it treat fairly investors who are not actually its customers. A good example was the proposal some years ago for fund management companies to ensure that the end investors received important communications like annual reports or proposals on which a vote was required. This was dropped when most fund management companies complained that this was impossible since they did not know who most of their end investors were.

It must be said, however, that the serious problems that have occurred in recent years have been at the interface between distributors and their customers. The defects were not a result of the legal structure of the products or inadequate compliance at the level of the fund management company but because there were intermediaries happy to sell the products because they appeared to offer high returns (an easy sell in an era of low interest rates) despite flawed investment strategies but not because they were non-compliant or fraudulent.

That is not to say that the distributors are not regulated. They too are expected to carry out all kinds of tests designed to ensure that the right product gets to the right customer – fact finds, best advice, and suitability, appropriateness (I have never been able to fathom the difference between these two), and categorisation of investors between retail and professional (sometimes an ill-defined boundary).

Too much box ticking

Meanwhile the fund management company, whoever that is defined as being, is burdened with all kinds of regulatory box ticking to ensure that it has in place the processes and routines to treat its largely unknown customers fairly. For example, trying to define whether a product is getting to the investors for whom it was designed or for whom it was not designed – how do you gather exhaustive or relevant data from distributors who have little interest in telling you that they have been unselective about their punters?

A lot of emphasis is placed on competence at all levels. The need to pin the blame on someone gave rise to the FCAs Senior Managers and Certification regime. This is complex and detailed regime which is set out in the 81 pages of the guide to FCA’s policy.

https://www.fca.org.uk/publication/policy/guide-for-fca-solo-regulated-firms.pdf.

Here the responsibilities for different activities are defined depending on whether the person is a senior manager or a less senior employee who must be certified as competent to do their job. This is great work for specialist trainers, most of whom certainly provide good and relevant material, but does it really achieve anything except provide certificates that let the fund management company off the regulatory hook? Do those much-certificated clerks sitting in their admin silos or working from home and following the procedures manuals religiously actually give much thought to whether they are treating customers fairly?

The FCA never tires

Never downhearted in its missionary zeal the FCA keeps bringing on ever more hoops for the regulated to jump through and more boxes to tick. Having failed to persuade the regulated to treat customers fairly it has just introduced a new hoop. This recent addition to the canon is called the ‘assessment of value’ where fund management companies where firms must indulge in self-flagellation to expiate their sins. This seems unlikely to have any effect apart from confusing investors, since it will not end in an auto-da-fe, burning at the stake employed by the Spanish inquisition for self-confessed heretics. See my blog https://markstgiles.com/2021/03/18/are-assessments-of-value-valueless/.

Plenty more work for compliance

In its description of ‘new consumer duty‘ the FCA finally acknowledges that most fund management firms don’t actually know who their investors are. But it means to proceed as if they did.

“Our proposals extend to firms that are involved in the manufacture or supply of products and services to retail clients, even if they do not have a direct relationship with the end customer.”

And, many more hours of preaching to the heathen, who remain stubbornly hard to convert. We are going to tell them exactly what to do.

“In the CP we are proposing the introduction of new rules, including a Consumer Principle, and setting out our proposals for the scope and structure of these rules, what they should cover and the outcomes they should seek to deliver.”

A plea for the future

So where from here? It may be that Brexit holds out some hope of less prescriptive regulation. The adoption of EU regulations that have become evermore civil code like, where reliance is placed on legal codes that are constantly updated and less on principles as in common law where courts interpret the law and create precedent. This may have driven the FCA to develop more detailed codes. But it is interesting to note that, if you read the FCAs key decisions that have resulted in fines or punishments, these are usually reliant on interpretation of failure to follow key principles rather on breaches of detailed regulations. More disclosure and lengthening rulebooks just result in lengthier and less comprehensible documentation for investors, as the reading of any annual report will show. It seems to me that greater simplicity would be just as effective but much less costly for investors who ultimately pay the price of regulation. Meanwhile, please, FCA stop churning out more regulations with the only result that firms will become more procedural and find it easier to keep busy with compliance games; and less concerned about real outcomes. Just get out there and stop obvious scams and rip offs and leave a predominantly honest and well-intentioned industry that has been remarkably free of scandals to get on with it.