The usefulness of collective investment funds/mutual funds is illustrated by global assets under management of around USD 69 trillion – but industry complexity is getting in the way of even greater success and depriving small savers of returns they can ill afford to ignore.

The Financial Conduct Authority notes that “there are 15.6 million UK adults with investible assets of £10,000 or more. Of these, 37% hold their assets entirely in cash, and a further 18% hold more than 75% in cash (Financial Lives Survey ). Over time, these consumers are at risk of having the purchasing power of their money eroded by inflation.” So – millions do nothing and stay with nice simple, familiar savings like the bank deposit or building society savings account. And if they are really brave enough to take a step forward, a cash ISA.

If they need the money in the immediate future or to meet a specific obligation, deposits are a useful short term home. But to assume that long term saving will be rewarded by staying in cash is quite irrational. A loaf of bread cost one old penny in 1914 – now the average loaf costs £1.35 – 324 times the 1914 price. At a typical current rate of interest on instant access savings of 0.011% an investment would only have increased in value by 13% over 100 years, leaving savers £1.22 short of the price of a loaf. Try cat food.

But even assuming that savers come to understand the opportunity cost of not investing in longer term assets, are the complexities of the fund market – which offers pooling of risk and access to diversified investments that ordinary investors need – just too off-putting?

Can ordinary investors get advice?

First, if choosing a fund from the thousands on offer in the UK the sector is too confusing, savers might look for advice. But they have first to find an adviser – not simple, for a number of reasons. For a start, there are around 5,500 retail investment firms are authorised by the Financial Conduct Authority to choose from. Then they have to be prepared to pay for the advice. I’ve taken a look at some IFA charges using the Which “Guide to the cost of advice” and also VouchedFor, a site that rates IFAs.

Most advisers will make a charge for the initial fact find and advice and this is usually rolled up into the subsequent transaction. The Which survey suggests that for an investment of £100,000 the cost may be between £6,500 and £8,500 split between initial cost and ongoing cost over five years. The Financial Conduct Authority review of retail investment markets shows that advisers charge an average of 2.4% of the amount for initial advice and 0.8% a year for ongoing advice or 1.9% a year with underlying product and portfolio charges factored in.

So, the total cost over five years would be 10%, using the FCA figure including the manager’s ongoing charge. And even if this expense is not too much of a deterrent, they may have considerable difficulty finding an adviser prepared to advise on sums of less than £75,000 or £100,000. Leaving aside the possibility of inheritance providing such sums, the probability that many can invest this amount seems low. HMRC data estimates for 2021/22 show that out of a total of 32,200,000 individual taxpayers, 83% were basic rate taxpayers.

Most advisory effort, therefore, is concentrated on the other 17%. So, advice may be difficult to find and may cost more than people are prepared to pay, so potential investors may simply give up.

Do they actually need advice?

Second, they may decide to try and choose a fund or funds for themselves. Here they face a choice of thousands of funds – taking one example, they might light upon FE TrustNet which lists 2,475 funds with a track record of five years or more.

Here they will find a bewildering series of names like ‘focus’, ‘thematic’, ‘select’, ’managed’, ‘income’ or ‘capital growth’ and unit class designations using letters from A to Z. For example, the “[Name withheld] Moderate Risk Unconstrained Strategic Multi Fund B Acc”. Phew!! (On a side note, the name of the fund is a factual description, which is better than the “sexed up” names of the past – but how many investors can understand what this fund is?)

How do ordinary investors know which fund to pick? If they had been clever enough to pick the winner over five years out of the 2,475 on offer listed in FE TRustNet, their return would have been 344.8%; but if they had been unlucky and picked the dog, they would only have had a return of only 18.9% over the same period. At the top end were mainly funds that had invested in big tech or the US – I don’t know what went wrong for the dog: but note that even the dog did better than being in cash.

But most ordinary long term investors are unlikely to want to pick and swirth between sector and geographic and currency exposures – they want someone else to do that for them. But that does not have to be done by a financial adviser. They really do want something like the Moderate Risk Unconstrained Strategic Multi Fund, if they understood what it was.

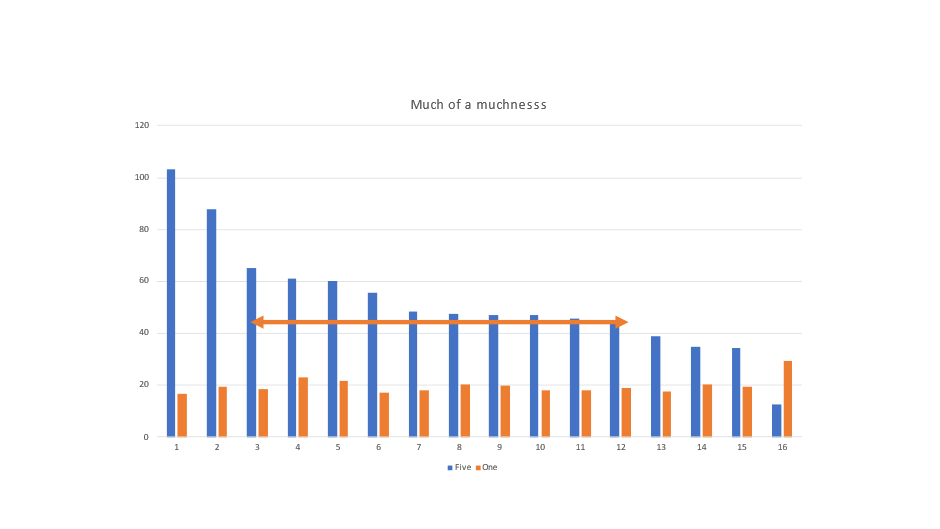

I have analysed the returns from funds from several fund management firms, well known to most investors, that approximate to the ‘balanced’ or ‘managed’ category which would ‘do the job for ordinary investors. As the chart (see below) shows, there is not a big variance in returns from numbers three to thirteen over one year and five years: however, numbers one and two are outstanding over five years but pretty much at or below average over one year, while fourteen, fifteen and sixteen at the bottom for 5 years were much better over one year. So no strategy or investment style lasts for ever.

The funds shown above are all actively managed funds, but to take a passively managed fund for contrast, the Vanguard Life Strategy Fund would have given a return over five years of 48% and the NEST 2040 Retirement Fund 50% over the same period. If you love ESG there will be a fund for you, but whose five year return are not yet in the data.

It is perfectly possible, if investors have ‘done it themselves’, to invest in a simple managed fund from a real well-known fund management company (no recommendation so no names) with no initial or exit charge and no advisory fee for a total all in cost over 5 years of 3.6% that gave a return over 5 years of 55%.

Let’s stop neglecting the small investor

It’s really time that many more fund management companies recognised that they should not neglect the great opportunities to be found by offering a straightforward service to non-advised small savers – rather than focusing on feeding the voracious advised market, which has a long chain of rent seeking intermediaries – with offerings of funds that have ever more specialist focus devised by the marketeers, and ever more incomprehensible names and unit classes.

I am glad to see that some of the more far sighted management companies are starting to do this. They will breed loyal small investors who will become big investors over time.

Some constructive ideas

- Management companies should try promoting to small savers a simple managed fund with diversification of asset classes and regions, with low charges and low investment limits that can be accessed directly from them using a simple intuitive app. Present it as a simple way for ordinary folk to save long term. Back in history that’s what the original unit trusts were for. An ISA wrapper as a free add-on too.

- Perhaps non-executive directors of management companies could ask why their company hasn’t done this or contemplated such a move.

- Maybe PIMFA, whose excellent report ‘Future of Advice’ that exhorts its members to “innovate to develop new lower cost services to provide effective advice to a wider market” should put its money where its mouth is and ask its members to provide practical pro bono simple guidance to small savers on simple long term saving

- Perhaps there may even be room for a well-publicised website which gave information about managed diversified funds that can be bought by direct access, at low cost and for small amounts at a time with some insights about their strategy. A site like Holly Mackay’s fun site Boring Money is right on the trend.

- Let’s not go to tokenised funds yet; but it looks as if tokenisation could play an increasing role in an industry that is complicated because it has simply transferred historical paper processes onto an IT system

One thought on “Complexity is the enemy of the simple”