Why are companies deciding to list in New York and why aren’t large investors supporting the market?

There has been a perfect storm of events that, in aggregate, had the unintended consequence of diminishing the attraction of the London stock market by curtailing the supply of long term investment by pension funds. The events I will describe has caused the slow death of defined benefit (‘DB’) pension funds, traditionally the largest investors in equities. To put it simply, there is as a result such a limited supply of long term demand for British equities that company valuations have declined. Since companies find it harder to raise new finance domestically on the best terms, they are naturally attracted to a market where they can. The main remaining source of demand is not from foreign portfolio investors, who regard the economic climate in Britain as unattractive; but rather from takeovers by international companies and private equity investors attracted by the low valuations. This steady decline of the relative market capitalisation of the London Stock Exchange, eroded by takeovers and a dearth of new issues makes London’s claim to be a leading hub for international finance less and less credible.

Accounting standards must take much of the blame.

Up until 2006 HMRC, under an ‘overfunding’ rule, required surpluses in DB schemes to be paid back to the sponsor with the sponsor responsible for making good any deficit. This was said the to prevent using pension contributions to avoid tax.

Traditionally, actuaries used a ‘smoothing’ method to reduce the peaks and troughs that might have been caused by market fluctuations which allowed deficits to be funded over long periods. This enabled schemes to remain invested predominantly in equities which were regarded as the best very long-term investment. DB schemes could take this very long view since they had had an infinite life with no final reckoning to be accounted for; that is to say that contributions from active members plus the returns (interest in actuarial terms) were used to fund retirement pensions in perpetuity. The only way they could come to an end was if the sponsoring employer went bust. The risk to pensioners from an inability to meet future pension liabilities was thus a result of the insolvency of the sponsoring employer, which would then be unable to continue its contributions upon which the solvency of a scheme depends; not from a flaw in the concept or operation of DB schemes. But the pension protection fund (‘PPF’) created in 2005 now exists to protect pensions in such an eventuality. It is funded by contributions from DB schemes, from the remaining assets of the fund and from anything it may be able to be recovered from the insolvent company.

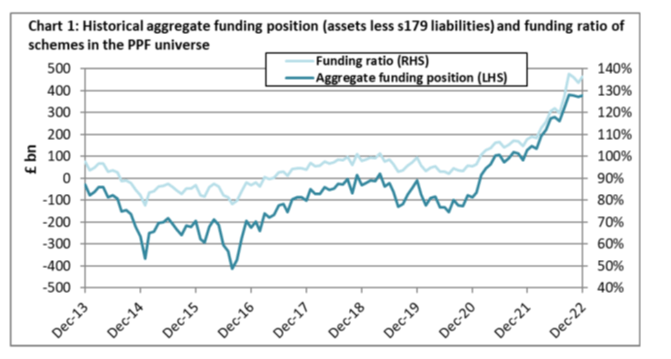

That all changed with FRS 17 (now FRS 102) in 2000. This accounting principle requires any deficit to be shown on the sponsoring company’s balance sheet as a liability but allows surpluses to be repaid only if their foundation documents have specific provision that permits this. The financial crisis of 2008-09 and resulting large falls in market values of equities caused most funds that had, at that time, 60% in equities (see chart 1 below) to move into technical deficit.

Chart 1

Source: PPF7800 Index

The adverse effect on the sponsoring company’s balance sheet worried finance directors, particularly since longevity was causing an increase in the number of pensioners in relation to active contributors.

The 2008 financial crisis accelerated the downward trend.

The exceptionally low interest environment caused by quantitative easing resulted in a discount factor that amplified liabilities, which, coupled with falls in values of markets, caused deficits first to increase and then to persist until further contributions had been made by sponsors to reduce the deficit and a rising market which started in 2020, after which surpluses began again.

Chart 2

Source: PPF7800 Index

Although there are a large number of private sector DB schemes still in existence (5532 according to date from the pensions regulator), this is misleading since a DB scheme is still technically recorded as such even if it is not accruing new contributions, for example paying pensions or accounting for deferred pension entitlements. The following shows this:

Chart 3. Open schemes are in a minority

Source: Pensions Regulator

CTNM = closed to new members

CTFA = closed to further accruals (for example where members are now offered a DC scheme)

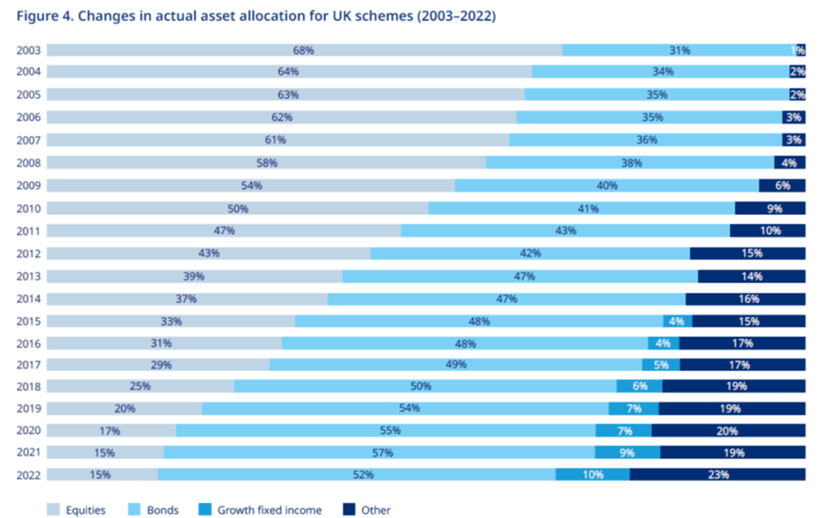

Furthermore, less than 20% of the total assets were held in open schemes (total £961 bn). Assuming that the other 80% would have been funded along LDI lines this would have made £191 bn available for equity investment. Based on the figure of 15% for equity exposure by pension funds generally (Chart 4) this would amount to a meagre £28 billion.

Equity holdings of pension funds had already been in continuous decline for 20 years.

However it was too late for equities to re-establish their position as the best long term investment for pensions. As can be seen below, equities had been losing ground and that trend accelerated after the financial crisis.

Chart 4

Source: Mercer

Companies found a way out of the pain.

Finance directors were dismayed at the effect pension liabilities were having on their balance sheets which was exacerbated by increased longevity, and they looked for ways to eliminate this. They were also influenced by the concept of ‘shareholder value’ so called from the title of an essay by Milton Friedman “A Friedman Doctrine: The Social Responsibility of Business is to Increase Its Profits.”, which could be taken to mean that the impact on profits of corporate contributions to pension funds and the need to fund technical deficits more quickly ran contrary to this doctrine of profit maximisation as an overriding objective..

There were two developments which offered a lifeline to companies for which pension deficits were regarded as a potential risk to the company’s revenues, given their obligation to keep the fund topped up if there was a deficit. This despite the fact that deficits were a result of theoretical actuarial calculations and would usually be self-correcting as interest rates used in the discounting of liabilities rose and equity markets recovered. There were few deficits that represented an immediate threat to payment of pensions.

Just close the DB scheme

One way out of the finance directors’ dilemma was to close the DB scheme to new entrants and offer new entrants only a defined contribution (‘DC’) scheme, where the liability falls only on the scheme member not on the sponsor. Over time this led to a steady increase in the proportion of liabilities attributable to those approaching retirement an already retired living longer, as the inflow of new members declined and brought the day of final reckoning closer. This left the DB scheme more reliant on markets; and for deficits, as a result, to become more unpredictable after the steady reduction in contributions from active members that would otherwise have helped support pensions in payment.

Try to achieve a perfect match of liabilities to assets

Associated with this was the concept of liability driven investment (LDI), which used a variety of techniques based on bonds and derivatives to eliminate the risks from market fluctuations and match more precisely the liabilities. Major insurance companies also sold a service that enabled sponsoring companies to offload their liabilities for a one-off payment or an annual premium, and asset managers offered to manage the LDI portion of the fund. The closed schemes now had finite lives and thus a defined final date for calculating residual liabilities – once the last pensioner had died. So, the value of long term returns on timeless schemes no longer had a place. Those who manage LDI schemes only have an interest in matching their liabilities as closely as possible to the diminishing liabilities, which means using bonds which have predictable returns. They have no interest in long term returns otherwise.

The public sector schemes don’t help, since they are not funded by investments.

Now, as the chart below shows, in 2021 most remaining DB schemes were for public sector employees. More than 80% public sector employees participated in DB schemes compared with only 7% in the private sector.

Chart 5 Private sector DB are dwarfed by public sector DB

However the majority of public sector schemes (NHS, teachers, firefighters, police, armed services and civil service) are unfunded, which means that their liabilities are not supported by a portfolio of investments and contributions of employees are paid to the exchequer which (or rather the taxpayers) assumes the liability to pay pensions. That liability supported by future government revenues was estimated in 2020 at £2.2 trillion according to HM treasury.

Local government schemes, which are funded, are small and fragmented, although they have in aggregate some £500 billion. They do invest up to three quarters of their funds in equities but more than 40% is invested overseas. Some consolidation of the 100 or so small schemes might help to give them the size to be serious investors in infrastructure for example, which requires chunky investments. But this will take time.

Can the new workplace pensions become major investors?

The replacement of DB schemes by DC schemes may offer some grounds for optimism; in particular, the growth of schemes under the requirement for mandatory contribution to workplace pensions since 2012. This encouraging development has brought into the pension system those who previously had had no pension apart from the basic state pension from 27% in 2012 to 67% in 2022. The total assets under management by the 21 master trusts which offer DC workplace pensions was close to £100 billion in February 2022. The largest three accounted for half of this; the largest was NEST, a government sponsored trust.

Australia may show the very long-term way forward.

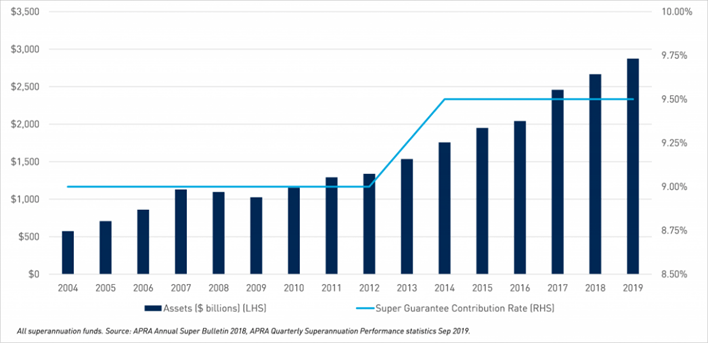

Could they be the agent for revival of the London stock market? Eventually, perhaps, but not in the short term. First they are not yet big enough to make an impact. Their rapid growth so far is in numbers of participants, 23 million as at February 2022 but not in the amount of funds managed not only because they are fairly new but because the contribution rate at 8% is far below typical rates for traditional DB schemes. At this rate it will take many more years for them to grow to the size of the Australian equivalent, the so called ‘superannuation funds’ (super funds) a compulsory system of superannuation support for Australian employees, paid for by employers, which came into full effect in 1992. The first year of this new regime boosted coverage to 80%. The percentage rate of contribution is currently 10% as of 1 July 2021, with further increases of 0.5% per year to come from 1 July 2022, until it reaches 12% from 1 July 2025 onwards. The total assets under management were $A3.3 trillion at the end of the September 2022. Now you are talking, but it’s taken 30 years to get there.

Chart 6 Australian super funds

The Australian super funds now account for more than the total market capitalisation of the Australian Stock Exchange (ASE) $A 2.5 trillion. The way assets are allocated may offer some hope for the UK’s DC schemes support for domestic markets. 52.4 per cent were investments in equities (21.7 per cent in Australian listed equities nearly 50% the market capitalisation of the ASE). The funds have also been strong supporters of infrastructure. Even the Public Sector Superannuation Scheme (PSS), which is a DB scheme, is funded and had 57% in equities as at March 2023.

The US 401(k) schemes are big investors in equities

The US version of the typical DC scheme is the 401(k) scheme first introduced in 1981 with total assets now $6.3 trillion and 67% invested in equities, and a generally recommended 20% of that in international markets. Participants in 401(k) schemes may select their own investments , typically from a range of mutual funds. This leads to active promotion by mutual fund groups which encourages savers to make higher contributions and build their pension pot faster.

British DC schemes are still small

The British version, at £100 billion, is as yet a minnow in comparison, which, even if it invested 100% of its assets in British shares, would account for less than 0.18% of the London Stock Exchange’s market capitalisation, even if such funds were to invest in Britain, which they do not appear to. The NEST 2040 retirement fund (growth phase) has an encouraging 55% exposure to global equities but none of the top ten holdings are of British companies but Apple, Microsoft, Amazon, Alphabet, Facebook etc. This tells its own story.

Allowing participants in workplace pensions more choice

Participants in mandatory workplace pensions permitted to select their own investments would most likely have a propensity to invest in domestic stocks as in Australia and the US. Although DC schemes in the UK may offer participants a choice of individual investments, the biggest master trusts offer only a range of managed portfolios, low risk, target date , higher risk etc. The management companies of collective investment schemes therefore have no interest in promoting savings in this way apart from trying to persuade the master trusts to invest in their funds. The major master trusts should be required to provide an option for savers to choose their own investments. This would not require legislative change but would fire up the promotional activities of fund management companies as is the case with ISAs. This could encourage pension savers to invest more than the statutory 8% of salary, which is unlikely to provide a sum at retirement adequate to provide a replacement income, and build the investment base faster.

A number of asset managers and others have called for FRS 17 to be scrapped but, by the time that could happen, it may be too late. There are other technical changes too that might make a difference. Less stringent listing rules, scrapping the pensions lifetime allowance and caps on annual contributions and other seemingly unrelated restrictions are all raised as helpful. But they are unlikely quickly to reverse the established trends discussed previously.

Get public sector schemes to invest

The real game changer would be to start funding public sector DB pensions or even shifting them over time towards DC. But is any politician or policymaker brave enough even to raise the question. Imagine the uproar? Just look what is happening in France as the unfortunate Macron tries to raise the pensionable age by a modest two years from 62 to 64. Would MPs even contemplate such changes given the rather generous pension scheme they awarded themselves; or indeed the Bank of England whose non-contributory scheme has an employer contribution rate of 52% of pensionable earnings; but has 80% of its investments in an LDI strategy? And how would Sir Humphrey , if called on to advise his Minister, marshal arguments to divert attention from his non-contributory final salary scheme to which he contributes 8% of his salary but the taxpayer adds a generous 30% (making him a Mandarin millionaire); and which has no investments to support his pension, just a taxpayer guarantee?

Is all this likely to save the day in the short run?

That all rather spoils the politicians’ dreams of finding a pot of gold at the end of a pensions rainbow with which to fund their fantasies. The truth is that in the unforgettable words of the outgoing Treasury Secretary in 2010 “there’s no money left”. So no short term fixes.