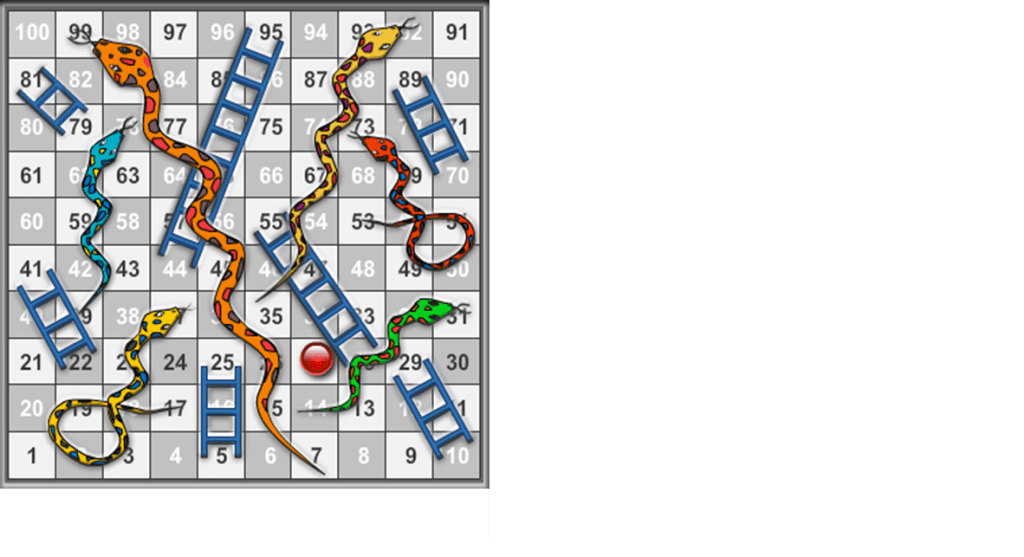

The housing market in Britain is like a game of Snakes and Ladders. If you are not lucky enough or have sufficient resources to be able to get on the ‘housing ladder’ you will most likely end up sliding down a snake that may lead you at the end to homelessness. The story goes like this.

Some history

In 1980, the then government passed legislation which enabled many local authority tenants to buy their home at a discounted rate. This followed a pledge in the 1979 Conservative Party manifesto to give local authority tenants the ‘right to buy’ their own home. The right to buy was conditional on the length of tenancy. It extended to local authority tenants of three or more years. A discount was offered to help tenants, who were often on low incomes. The minimum discount was 33%, increasing by 1% for every further year of tenancy above three years. The maximum discount could not exceed £50,000 (equivalent to just over £200,000 in 2022). These discounts had to be paid back if the property was sold within five years. Tenants also had the right to a mortgage from their local authority. The Housing and Building Control Act 1984 extended the scheme to tenants on long leases and reduced the tenure requirement to two years. It also increased the discount to a maximum of 60% after 30 years tenancy.

This unsurprisingly proved to be very attractive to tenants. Since the start of the Right to Buy scheme in 1980, until 31 March 2022, there have been over 2,003,239 sales to tenants through the Right to Buy scheme. But because of the regulations most of the proceeds went to the Treasury rather than to Local Authorities to build replacements.

Regulations 2003 (as amended) The regulations require that, in short:

receipts arising from Right to Buy (and similar) sales may be retained to cover the cost of transacting the sales and to cover the debt on the properties sold, but a proportion of the remainder must be surrendered to central Government;

• receipts arising from all other disposals may be retained in full provided they are spent on affordable housing, regeneration or the paying down of housing debt (each of which is defined in the regulations).

In other words, Local Authorities had to give up most of the proceeds of sales under Right to Buy which they couldn’t recycle into building more social housing. The Chartered Institute of Housing’s UK Housing Review in 2021 found the Treasury had made £47bn on sales to tenants under Right to Buy.

Thousands were sold and not replaced

Council housing as opposed to affordable housing built by housing associations) went into steep decline. As the chart below shows. Not only was the existing stock depleted but fewer and fewer new houses were built.. By 1990 hardly any were being built at all compared with 150,000 a year in the 1950s; and in 2022 only 7,500 new social homes were built.

The history of council housing

A combination of the reduction in the rate of construction of social housing and sale of local authority housing led to a reduction in the availability of social housing in England.Government figures show a reduction from 5.5mn in 1980 to 4.1mn in 2021.

[1] Right to buy: Past, present and future :House of Lords Library published Friday, 17 June, 2022

Effect of the reduction

This reduction is roughly equal to the number of council houses sold under Right to Buy and not replaced. Nor did affordable housing make up the deficiency as the chart shows. Affordable rents (approximately 80% of market rents) are higher that social rent (approximately 50% of market rents). So, houses with affordable rents are no real substitute for social rentals and in areas where market rents are high affordable rents can be unaffordable and often not covered by local housing allowance.. Also tenure is usually for 5 years or shorter as opposed to a longer term or permanent tenure for social housing.

Could local authorities borrow to build?

Local Authorities were also subject to a borrowing cap, which was finally removed in 2018. Many local authorities – 94 percent of those with retained housing stock – plan to use this power to borrow to invest in new homes. The Public Works Loans Board provides, as it did during the great post-war council housing boom, the means by which the capital required can be cheaply accessed.. Local Authorities can also issue bonds in the commercial market, where the Municipal Bonds Agency set up in 2014 was designed to help. The idea of credit enhancement through issue of bonds by the agency guaranteed proportionately by the Local Authorities to which it had lent has not been a success. Its operation should be improved.

But with so many Local Authorities in financial difficulties it is hard for them to be able to comply with the prudential borrowing limits imposed by the CIPFA Prudential Code requiring them to have regard to the Prudential Code when carrying out their duties in England and Wales under Part 1 of the Local Government Act 2003. The objectives of the Prudential Code are to ensure, within this clear framework, that the capital investment plans of local authorities are affordable, prudent and sustainable. Given that a majority of Local Authorities are going to find it hard even to balance budgets, it is hard to see how they will be able to comply.

[1] The Prudential Code For Capital Finance In Local Authorities (2021 Edition)

How do you find some where to live?

So how to get somewhere to live assuming that you can’t afford to buy? Not much chance of a council house given that the waiting list as at January 2023 was 1,200,000[1]

[1] https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/social-housing-lettings-in-england-april-2021-to-march-2022/social-housing-lettings-in-england-tenants-april-2021-to-march-2022

So where does the snake take you next?

So affordable housing as opposed to social housing? It’s hard to find national data but anecdotal evidence suggests that it is not that easy to find, supply is pretty limited and not necessarily affordable even if you can find a place that is adequate for a family. The government’s statistics tend to blur the difference between social and affordable and focus on the new additions but whichever way you look at it there are just not enough of them. The chart shows new starts by type of tenure. There is an encouraging increase in the social category.

Source: National statistics Affordable housing supply in England: 2021 to 2022

The terminological confusion between social and affordable is illustrated by the chart where the category ‘other unknown’ is significant. The confusion is such that Government Statistical Service tried to harmonise it, saying it had ‘identified concerns around a lack of clarity on affordable housing statistics in the UK, and the extent to which they are comparable. Housing policy is devolved, and the definitions of affordable housing and associated terminology differ between the four countries of the UK.’

Hopefully the supply of affordable housing will increase

The government’s Affordable Homes Programme 2021-2026 is designed:

To increase access to secure and decent homes for households who cannot otherwise afford to buy or rent a home at the market price; to increase homeownership across England amongst those that might not otherwise be able to buy their own home; and to achieve positive impacts for wider communities and society.’

It aims to deliver 126,000 homes in England outside London and 35,000 homes in London). The funding is expected to support starts on site between 2021 and 2026, with completions expected by 2028 for most projects. Approximately 50% of units funded via Strategic Partnerships will be for owner occupation (mainly Shared Ownership) and 50% for rental tenures (most with a new right to shared ownership attached).[1] This programme would deliver 181,000 hew homes over five years compared with estimates of a need for 90,000 new affordable homes a year by Shelter 450,000 over five years, a deficit of 350,000. Better than nothing

[1] Scoping Report for the Evaluation of the Affordable Homes Programme 2021-2026 August 2022

So where next?

The private rented sector is your next place to go. Back in history the private rented sector accounted for around 90% of the 6.3 million stock of dwellings in 1901. By 1986 the private rented sector had declined to smallest size ever as by which date it had been reduced to 1.6 million dwellings, or just 8.7 % of the housing stock in England. But something interesting started to happen as shown in study by the University of York ‘The fall and rise of the private rented sector in England.’

“The decade from 1991 to 2001 saw an overall reversal in the contraction of private renting. The number of privately renting households increased by 65 per cent to 3.7 million, equivalent to 17.1 per cent of all households in 2011. The number of owner occupiers increased very slightly but decreased as a proportion of all households to 65.0 per cent; and social renting decreased to 3.9 million, or 17.9 per cent of all households.“

Thus the private rental sector has reached unprecedented post war levels. By the end of 2022, around 5.4 million homes, up from 3.7 million homes in 2001 in Great Britain were privately rented. The number of privately rented homes grew by 126% between 2001 and 2020 fuelled by the ‘buy to let’ boom. By 2022 the private rented sector was larger that the socially rented sector[1]

This change may be a result of the reduced supply of social housing as a result of Right to Buy. It is interesting to note that a survey by the magazine Inside Housing in 2015 suggested that around 40 per cent of homes bought under Right to Buy were now in the private rental sector. Therefore, the unintended outcome of over incentivising the least well-off living in social housing to buy at big discounts has been to turn them into rentiers, the very epitome of capitalists,

Not all private landlords are ‘wicked landlords’ and many take care to ensure that their properties are well maintained. While no fault evictions hit the headlines, the survey by National Statistics[2] shows that only 4% fell into this category compared with 77% who wanted to move. Nonetheless private rental is generally more expensive than affordable or social rental and it is hard to find homes where rent can be covered by local housing allowance.

Evidence suggests that the stock of private rentals is declining with landlords under pressure from changes in taxation and rising interest rates deciding to cash in their asset and sell up. Another factor that will contribute to housing shortage.

[1] National statistics English Housing Survey 2021 to 2022: private rented sector[2] National statistics English Housing Survey 2021 to 2022: private rented sector

Where next?

When all options are exhausted. You can’t afford to buy, can’t get on the waiting list for social housing or cannot find a private rental you can afford you can always declare yourself homeless and ask your Local Authority to house you, which they are statutorily obliged to do. Not only is this distressing for those who are forced into homelessness but an enormous burden on Local Authority finances forcing them to cut expenditure on desirable but not essential facilities like libraries and sports fields, since they have a statutory obligation to house the genuinely homeless..

Analysis from the LGA, which represent councils across England, reveals that the number of households living in temporary accommodation has risen by 89 per cent over the past decade to 104,000 households at the end of March 2023 – the highest figures since records began in 1998 – costing councils at least £1.74 billion in 2022/23. Asylum and resettlement schemes are also adding to supply and demand issues.

The last resort

Government data shows nearly 3,000 sleeping rough and 15,000 in hostels [1] as at September 2023. It all starts at the beginning. This is an outcome of a failure to provide sufficient housing for a growing population

[1] Ending Rough Sleeping Data Framework, September 2023

A solution

Start at the beginning more than 100 years ago. A series of housing acts through the 1920s and 1930s made it the responsibility of local authorities to develop new housing and rented accommodation where it was needed by working people and to clear slums. Local Authorities were also given substantial grants to help finance this task. Under the provisions of the inter-war Housing Acts local councils built a total of 1.1 million homes.[1] This had profoundly positive social consequences.

[1] https://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/transformingsociety/towncountry/towns/overview/councilhousing/

So get local authorities to do the same again. Build more council houses. This solution is not as easy as it sounds. There are so many overlapping problems that need to be addressed in a coordinated way or joined up in the fashionable phrase

lack of a clear national strategy

belief that short term gimmicks will solve the problem

a Byzantine web of national and local regulations from planning to environmental

opposition from local residents who can use the courts to delay and deter developers

self interest of major building companies who thrive on complexity and delay

no financial gain for local authorities in giving planning permission only to make landowners and builders rich

the poor quality of many residential developments with ever smaller houses to cram more into the available space – tomorrow’s slums?

ever changing ministerial responsibility – 16 housing ministers in the last 13 years.

sticking plaster measures like ‘help to buy’ which just stoked the fire of house price rises

half baked ideas like the Lifetime ISA that gave taxpayer funded bonuses to those saving to buy a house

The president of the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) in late 2023 put it better than I can:

“The government has to get a grip on this housing crisis – it demands urgent action. We need continuity, the development of a strategic plan and certainty to ensure homes and places are planned, designed and built to meet the needs of current and future communities.”

Forlorn hope? The present government clearly cannot think further ahead than this year. Would an incoming Labour government be prepared to make rather boring longer-term solutions a priority and actually spend time trying to identify and implement them. No headlines here.